What Is a Special Thing the Blue Spotted Sting Ray Can Do

Untitled

provided by Animal Diversity Web

The body of Taeniura lymma is made completely out of cartilage and contains no bone whatsoever. The stinging barbs on its tail can be regenerated if broken off. One interesting fact about the venom that is contained within the stinging barbs is that it can be broken down by heat. Therefore, if you ever encounter one of these magnificent animals and happen to get stung, immediately soak the wound in hot water in order to break down the venom and reduce the pain. Another interesting fact about Taeniura lymma is that it is one of the few species of rays that can retain their urine.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Behavior

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Taeniura lymma uses electroreception to communicate with other members of its species. Blue-spotted stingrays,use strucutres called the ampullae of Lorenzini, which allow them to detect slight electrical impulses within the water. This electroreception is often used as a means of recognizing members of the same species.

Communication Channels: chemical ; electric

Perception Channels: visual ; tactile ; chemical ; electric

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Conservation Status

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Although this species is very wide ranging and common, it is subject to human-induced problems because of capture by inshore fisheries and its attractiveness for the marine aquarium fish trade. Another major threat to this species is the destruction of its coral reef habitat. Without a habitat in which to live, this species may be pushed to extinction along with other species of the coral reef habitat.

US Migratory Bird Act: no special status

US Federal List: no special status

CITES: no special status

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: near threatened

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Life Cycle

provided by Animal Diversity Web

When blue-spotted stingrays are born, they hatch out of egg cases and are pale gray or brown and are spotted with black or rusty red and white. These patterns and markings are distinct to each individual within a litter. As adults, they are olive-gray or gray-brown to yellow dorsally and white ventrally with numerous blue spots. When born, the young stingrays are about nine cm long and can grow to around 25cm as adults. The young are born out of egg cases with a soft tail that is encases in a thin layer of skin to prevent injury to the mother during birth. The skin is eventually lost and the tail is used as a protective mechanism.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Benefits

provided by Animal Diversity Web

The sting that of blue-spotted stingrays may be very painful.

Negative Impacts: injures humans (bites or stings)

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Benefits

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Taeniura lymma is a popular aquarium pet. Their beautiful coloration makes them a prime candidate for an aquarium pet. In Australia, Taeniura lymma is often eaten and hunted for its meat.

Positive Impacts: pet trade

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Associations

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Taeniura lymma plays an important role in their ecosystem. Taeniura lymma is a secondary consumer. It feeds on nekton such as bony fish. It also feeds on zoobenthos organisms including benthic crustaceans like crabs, shrimp/prawns, and worms such as polychaetes.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Trophic Strategy

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Taeniura lymma has very distinct feeding behaviors. During high tide, it migrates in groups into shallow sandy areas of tidal flats to feed on sand worms, shrimps, hermit crabs, and small fishes. At low tide it recedes back into the ocean, usually alone to hide in the coral crevices of the reef.

Blue-spotted stingrays will feed on many things such as bony fish, crabs, shrimp, polychaetes and other benthic invertebrates. Since the mouth is located on the underside of the body, food is trapped by pressing the prey into the substrate with their discs. The food is then directed into the mouth by maneuvering the disc over the prey.

Taeniura lymma can detect its prey through an electroreceptor system. The nostrils are partly covered with a broad fleshy lobe, known as the internasal flap. This is covered in sensory pores and extends to the mouth. These pores form part of the ampullae of Lorenzini (the electrorecption system.) This electroreceptor system can detect electrical fields produced by the prey. This electroreceptor system cannot only be used to detect prey but can also be used to detect predators and other members of the same species.

Animal Foods: fish; aquatic or marine worms; aquatic crustaceans; other marine invertebrates

Primary Diet: carnivore (Piscivore , Eats non-insect arthropods)

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Distribution

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Taeniura lymma, commonly known as blue-spotted stingrays, is found primarily in the Indo-west Pacific. They may be found in shallow continental shelf waters ranging from temperate to tropical seas. They prefer areas with sandy or sedimentary substrates in which they bury themselves. Sightings of Taeniura lymma have been recorded in Australia in shallow tropical marine waters from Ningaloo Reef, Western Australia to Bundaberg, Queensland. They can be found at depths of up to 25 m and have also been recorded to range in location from southern Africa and the Red Sea to the Solomon Islands.

Biogeographic Regions: australian (Native ); indian ocean (Native ); pacific ocean (Native )

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Habitat

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Taeniura lymma is found on sandy bottoms around coral reefs. These rays like to bury themselves just underneath the sand where they will feed on various invertebrates. They usually are found on shallow continental shelves; however, they have also been observed around coral rubble and shipwreck debris at depths of 20-25m deep. Divers and snokelers will often detect this ray by its distinctive ribbon-like tail poking out from a crack in the coral. These rays are most abundant inshore.

Range depth: 25 (high) m.

Habitat Regions: tropical ; saltwater or marine

Aquatic Biomes: benthic ; reef

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Life Expectancy

provided by Animal Diversity Web

The lifespan of Taeniura lymma is still unknown.

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Morphology

provided by Animal Diversity Web

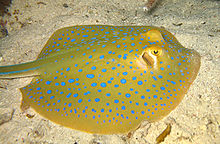

Taeniura lymma is a colorful stingray with distinct, large, bright blue spots on its oval, elongated body. The snout is rounded and angular with broad outer corners. The tail tapers and can be equal to or slightly less than the body length when intact. Its caudal fin is broad and reaches to the tip of the tail. At the tip of the tail are two sharp venomous spines which permit this ray to strike at enemies forward of its head. The tail of Taeniura lymma can be easily recognized by the blue side-stripes found on either side. It has large spiracles that lie very close to its large eyes. It can grow to a disc diameter of about 25 cm but has been reported as being as large as 95 cm in diameter. The mouth is found on the underside of the body along with the gills. Within the mouth are two plates, which are used for crushing the shells of crabs, prawns, and mollusks.

Range length: 95 (high) cm.

Average length: 25 cm.

Other Physical Features: ectothermic ; bilateral symmetry ; venomous

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Associations

provided by Animal Diversity Web

The most dangerous predator to blue-spotted stingrays are human beings. Blue-spotted stingrays are a popular ray to have in aquarium tanks. However, Taeniura lymma is very hard to take care of in an at-home aquarium. Besides humans, the only other type of predator known to this species of stingrays is the hammerhead shark. The hammerhead shark uses the cartilaginous projections form the side of their heads to pin them down to the bottom of the substrate while taking bites from the stingray's disc. The hammerhead is able to avoid being stung by the poisonous spines on the rays tail by pinning the stingray down.

Known Predators:

- great hammerheads (Sphyrna lewini)

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Reproduction

provided by Animal Diversity Web

Taeniura lymma is ovoviviparous. This means that the embryo is nourished by the yolk and the eggs are retained within the female until they hatch. The ray produces about seven live young in every litter. Each juvenile is born with the distinctive blue markings of its parents in miniature. In courtship, the male often follows the female with his acutely sensitive nose close to her cloaca in search of a chemical signal that the female will emit. Courtship usually includes some sort of nibbling or biting of the disc. The teeth of the male are used to hold the female in place during population. The male fertilizes the female via internal fertilization through the use of their claspers. The breeding season is usually in late spring through the summer and gestation can be anywhere from 4 months to a year.

Because only about seven live young are produced in each litter, this species is highly vulnerable to population collapses from overfishing, habitat loss and the pet trade. They also have a long gestation period making them even more susceptible to population collapse.

Breeding season: late spring throught summer

Average number of offspring: 7.

Range gestation period: 4 to 12 months.

Key Reproductive Features: iteroparous ; gonochoric/gonochoristic/dioecious (sexes separate); sexual ; fertilization (Internal ); ovoviviparous

- license

- cc-by-nc-sa-3.0

- copyright

- The Regents of the University of Michigan and its licensors

- bibliographic citation

- Miller, J. 2002. "Taeniura lymma" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 27, 2013 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/site/accounts/information/Taeniura_lymma.html

- author

- Jennifer Miller, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Randall L. Morrison, Western Maryland College

- editor

- Matthew Wund, University of Michigan-Ann Arbor

Biology

provided by Arkive

Blue-spotted stingrays live alone or in small groups (6), migrating in large schools into shallow sandy areas on the rising tide in order to feed, and dispersing back into the ocean as the tide falls to shelter in the coral crevices of the reef (5) (7). Feeding most commonly occurs during the day, but sometimes also at night (6), and the diet consists largely of worms, shrimps, crabs, molluscs and small fish (5). Prey is often detected through electroreception, a system which senses the electrical fields produced by the prey (5). Not all small fish and invertebrates are potential prey, as blue-spotted stingrays can often be found at 'cleaning stations', areas of reef where large fish line up and tiny fish or shrimp pick off their dead skin and parasites (6). In courtship, males often follow females, using their acutely sensitive 'nose' to detect a chemical signal emitted by the female that indicates she is receptive. Breeding occurs from late spring through the summer, and gestation can last anything from four months to a year (5). Reproduction is ovoviviparous, meaning females give birth to live pups that have hatched from egg cases inside the uterus (6). Up to seven pups are born per litter and each juvenile is born with the distinctive blue markings of its parents in miniature (7).

Conservation

provided by Arkive

Presently, this stingray is classified only as Lower Risk/near threatened (LR/nt) on the IUCN Red List 2004, and no direct conservation measures are currently in place for the species (1).

Description

provided by Arkive

This colourful stingray is immediately recognisable by the large, bright, iridescent blue spots that adorn its oval, elongated body (3) (4). Distinctive blue stripes also run along either side of the tail, which is equipped with one or two sharp venomous spines at the tip, used by the ray to fend off predators (5). Indeed, the brightly-coloured skin acts as 'warning colouration' to alert other animals that it is venomous (6). The snout is rounded and the mouth is found on the underside of the body, along with the gills (5), perfect for scooping up animals hiding in the sand (6). Two plates exist within the mouth that are adapted for crushing the shells of crabs, prawns and molluscs (5). The upper surface of the body disc is grey-brown to yellow, olive-green or reddish brown, while the underside is white (3). Thus, when viewed from below the white belly blends in with the sunny waters above and when viewed from above, the dark, mottled back blends in with the dark ocean floor below (6).

Habitat

provided by Arkive

Commonly found on the sandy or rocky bottoms of coral reefs, in shallow continental shelf waters, to depths of 20 m (3) (5). While usually inhabiting the deeper reef areas, where it hides in reef caves, under tabletop corals and overhangs, this stingray moves up to shallower reef flats and lagoons at high tide. Unlike most stingrays, blue-spotted stingrays rarely bury themselves in the sand (6).

Range

provided by Arkive

Found in the Indo-West Pacific: ranging from South East Africa and the Red sea to the Solomon Islands, north to southern Japan and south to northern Australia (3).

Status

provided by Arkive

Classified as Lower Risk/near threatened (LR/nt) on the IUCN Red List (1).

Threats

provided by Arkive

Despite being both wide-ranging and common, the blue-spotted stingray is subject to a variety of human-imposed threats (1). Widespread destruction of coral reef habitat probably poses the most significant threat to the species (1). Harm is caused by poisoning through farm pesticides and fertilizers running into the sea, by dynamite fishing, and by cyanide, used to capture reef animals for the pet trade (6). This ray is hunted throughout its range by inshore fisheries and its beautiful colouration makes it an attractive candidate for an aquarium pet (5) (6). However, this species does not survive well as a pet, outgrowing most home aquariums (6). With such a low reproductive rate, consisting of long gestation periods and small litters, the blue-spotted stingray is particularly vulnerable to population collapses caused by over-fishing, habitat loss and the pet trade (5).

Diagnostic Description

provided by Fishbase

A colorful stingray with large bright blue spots on an oval, elongated disc and with blue side-stripes along the tail; snout rounded and angular, disc with broadly rounded outer corners, and tail stout, tapering and less than twice body length when intact, with a broad lower caudal finfold reaching the tail tip; disc with no large thorns but with small, flat denticles along midback (in adults); usually 1 medium-sized sting on tail further behind base than in most stingrays (Ref. 5578). Grey-brown to yellow, olive-green or reddish brown dorsally, white ventrally (Ref. 5578).

- Recorder

- Cristina V. Garilao

Life Cycle

provided by Fishbase

Exhibit ovoviparity (aplacental viviparity), with embryos feeding initially on yolk, then receiving additional nourishment from the mother by indirect absorption of uterine fluid enriched with mucus, fat or protein through specialised structures (Ref. 50449). Distinct pairing with embrace (Ref. 205). Distinct pairing with embrace (Ref. 205). Bears up to 7 young (Ref. 5578, 12951).

- Recorder

- Cristina V. Garilao

Trophic Strategy

provided by Fishbase

Found on the continental shelf (Ref. 75154). Feeds on fish and invertebrates (Ref. 5578).

Biology

provided by Fishbase

Occurs around coral reefs (Ref. 6871, 58534). Migrates in groups into shallow sandy areas during the rising tide to feed on mollusks, worms, shrimps, and crabs; disperses on falling tide to seek shelter in caves and under ledges (Ref. 6871). Rarely found buried under the sand (Ref. 12951). Ovoviviparous (Ref. 50449). Small specimens are popular among marine aquarists (Ref. 5578). Does not do well in aquariums (Ref. 12951). Maximum length about 70 cm TL (Ref. 30573). Reports of specimens reaching 240 cm TL are probably inaccurate (Ref. 6871). Commonly caught by fisheries operating over shallow coral reefs and probably adversely affected by dynamite fishing. Utilized widely for its meat (Ref.58048).

- Recorder

- Estelita Emily Capuli

Importance

provided by Fishbase

fisheries: commercial; gamefish: yes; aquarium: commercial

- Recorder

- Estelita Emily Capuli

Bluespotted ribbontail ray

provided by wikipedia EN

The bluespotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma) is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae. Found from the intertidal zone to a depth of 30 m (100 ft), this species is common throughout the tropical Indian and western Pacific Oceans in nearshore, coral reef-associated habitats. It is a fairly small ray, not exceeding 35 cm (14 in) in width, with a mostly smooth, oval pectoral fin disc, large protruding eyes, and a relatively short and thick tail with a deep fin fold underneath. It can be easily identified by its striking color pattern of many electric blue spots on a yellowish background, with a pair of blue stripes on the tail.

At night, small groups of bluespotted ribbontail rays follow the rising tide onto sandy flats to root for small benthic invertebrates and bony fishes in the sediment. When the tide recedes, the rays separate and withdraw to shelters on the reef. Reproduction is aplacental viviparous, with females giving birth to litters of up to seven young. This ray is capable of injuring humans with its venomous tail spines, though it prefers to flee if threatened. Because of its beauty and size, the bluespotted ribbontail ray is popular with private aquarists despite being poorly suited to captivity.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

A bluespotted ribbontail ray in Komodo National Park, Indonesia.

The bluespotted ribbontail ray was originally described as Raja lymma by Swedish naturalist Peter Forsskål, in his 1775 Descriptiones Animalium quae in itinere ad maris australis terras per annos 1772, 1773, et 1774 suscepto collegit, observavit, et delineavit Joannes Reinlioldus Forster, etc., curante Henrico Lichtenstein.[2] The specific epithet lymma means "dirt".[3] Forsskål did not designate a type specimen.[2] In 1837, German biologists Johannes Peter Müller and Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle created the genus Taeniura for Trygon ornatus, now known to be a junior synonym of this species.[4] [5]

Other common names used for this species include bluespotted ray, bluespotted fantail ray, bluespotted lagoon ray, bluespotted stingray, fantail ray, lesser fantail ray, lagoon ray, reef ray, ribbon-tailed stingray, and ribbontail stingray.[5] Morphological examination has suggested that the bluespotted ribbontail ray is more closely related to the amphi-American Himantura (H. pacifica and H. schmardae) and the river stingrays (Potamotrygonidae) than to the congeneric blotched fantail ray (T. meyeni), which is closer to Dasyatis and Indo-Pacific Himantura.[6]

Distribution and habitat

Widespread in the nearshore waters of the tropical Indo-Pacific region, the bluespotted ribbontail ray has a range that extends around the periphery of the Indian Ocean from South Africa to the Arabian Peninsula to Southeast Asia, including Madagascar, Mauritius, Zanzibar, the Seychelles, Sri Lanka, and the Maldives. It is rare in the Persian Gulf and Gulf of Oman.[1] [7] In the Pacific Ocean, this species is found from the Philippines to northern Australia, as well as around numerous Melanesian and Polynesian islands as far east as the Solomon Islands.[1] Rarely found deeper than 30 m (100 ft), the bluespotted ribbontail ray is a bottom-dwelling species that frequents coral reefs and adjacent sandy flats. It is also commonly encountered in the intertidal zone and tidal pools, and has been sighted near seagrass beds.[1] [8] Every summer, considerable numbers of bluespotted ribbontail rays arrive off South Africa.[3]

Description

The bluespotted ribbontail ray has distinctive coloration.

The pectoral fin disc of the bluespotted ribbontail ray is oval in shape, around four-fifths as wide as long, with a rounded to broadly angular snout. The large, protruding eyes are immediately followed by the broad spiracles. There is a narrow flap of skin between the nares with a fringed posterior margin, reaching past the mouth. The lower jaw dips at the middle and deep furrows are present at the mouth corners. There are 15–24 tooth rows in either jaw, arranged into pavement-like plates, and two large papillae on the floor of the mouth.[3] [9] The pelvic fins are narrow and angular. The thick, depressed tail measures about 1.5 times the disc length and bears one or two (usually two) serrated spines well behind the tail base; there is a deep fin fold on the ventral surface, reaching the tip of the tail, and a low midline ridge on the upper surface.[7] [9]

The skin is generally smooth, save for perhaps a scattering of small thorns on the middle of the back.[9] The dorsal coloration is striking, consisting of numerous circular, neon blue spots on a yellowish brown or green background; the spots vary in size, becoming smaller and denser towards the disc margin. The tail has two stripes of the same blue running along each side as far as the spines. The eyes are bright yellow and the belly is white.[3] [8] Individuals found off southern Africa may lack the blue tail stripes.[10] The bluespotted ribbontail ray grows to 35 cm (14 in) across, 80 cm (31 in) long, and 5 kg (11 lb).[5] [11]

Biology and ecology

The bluespotted ribbontail ray hides amongst coral during the day.

One of the most abundant stingrays inhabiting Indo-Pacific reefs, the bluespotted ribbontail ray generally spends the day hidden alone inside caves or under coral ledges or other debris (including from shipwrecks), often with only its tail showing.[8] [9] [12] At night, small groups assemble and swim onto shallow sandy flats with the rising tide to feed. Unlike many other stingrays, this species seldom buries itself in sand.[13] The bluespotted ribbontail ray excavates sand pits in search of molluscs, polychaete worms, shrimps, crabs, and small benthic bony fishes; when prey is located, it is trapped by the body of the ray and maneuvered into the mouth with the disc. Other fishes, such as goatfish, frequently follow foraging rays, seeking food missed by the ray.[10] [14]

Breeding in the bluespotted ribbontail ray occurs from late spring to summer; the male follows the female and nips at her disc, eventually biting and holding onto her for copulation.[14] There is also a documented instance of a male holding onto the disc of a smaller male bluespotted stingray (Dasyatis kuhlii), in a possible case of mistaken identity. Adult males have been observed gathering in shallow water, which may relate to reproduction.[12] : 88 Like other stingrays, this species is aplacental viviparous: the embryos are initially sustained by yolk, which later in development is supplemented by histotroph ("uterine milk", containing mucus, fat, and proteins) produced by the mother. The gestation period is uncertain, but is thought to be between four and twelve months long. Females bear litters of up to seven young, each a miniature version of the adult measuring around 13–14 cm (5.1–5.5 in) across.[13] [15] Males attain sexual maturity at a disc width of 20–21 cm (7.9–8.3 in); the maturation size of females is unknown.[5] [15]

Known predators of the bluespotted ribbontail ray include hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna) and bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops); it is also potentially preyed upon by other large fishes and marine mammals.[13] [16] When threatened, this ray tends to flee at high speed in a zigzag pattern, to throw off pursuers.[8] Numerous parasites have been identified from this species: the tapeworms Aberrapex manjajiae,[17] Anthobothrium taeniuri,[18] Cephalobothrium taeniurai,[19] Echinobothrium elegans and E. helmymohamedi,[20] [21] Kotorelliella jonesi,[22] Polypocephalus saoudi,[23] and Rhinebothrium ghardaguensis and R. taeniuri,[24] the monogeneans Decacotyle lymmae,[25] Empruthotrema quindecima,[26] Entobdella australis,[27] and Pseudohexabothrium taeniurae,[28] the flatworms Pedunculacetabulum ghardaguensis and Anaporrhutum albidum,[29] [30] the nematode Mawsonascaris australis,[31] the copepod Sheina orri,[32] and the protozoan Trypanosoma taeniurae.[33] This ray has been observed soliciting cleanings from the bluestreak cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus) by raising the margins of its disc and pelvic fins.[12]

Human interactions

A bluespotted ribbontail ray being housed within an aquarium in which they rarely live long.

While timid and innocuous towards humans, the bluespotted ribbontail ray is capable of inflicting an excruciating wound with its venomous tail spines.[13] Its attractive appearance and relatively small size has resulted in its being the most common stingray found in the home aquarium trade.[34] It seldom fares well in captivity and few hobbyists are able to maintain one for long.[12] Many specimens refuse to feed in the aquarium, and seemingly healthy individuals often inexplicably die or stop feeding.[12] A higher degree of success has been achieved by public aquariums and a breeding project is maintained by the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (for example, a total of 15 pups were born at Lisbon Oceanarium from 2011 to 2013).[35] The bluespotted ribbontail ray is utilized as food in East Africa, Southeast Asia, and Australia; it is captured intentionally or incidentally using gillnets, longlines, spears, and fence traps.[1] [15]

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed the bluespotted ribbontail ray as Least Concern. Although relatively common and widely distributed, this species faces continuing degradation of its coral reef habitat throughout its range, from development and destructive fishing practices using cyanide or dynamite. Its populations are under heavy pressure by artisanal and commercial fisheries, and by local collecting for the aquarium trade.[1]

References

- ^ a b c d e f Sherman, C.S.; Simpfendorfer, C.; Bin Ali, A.; Derrick, D.; Dharmadi, Fahmi, Fernando, D.; Haque, A.B.; Maung, A.; Seyha, L.; Tanay, D.; Utzurrum, J.A.T.; Vo, V.Q.; Yuneni, R.R. (2021). "Taeniura lymma". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2021: e.T116850766A116851089. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2021-1.RLTS.T116850766A116851089.en . Retrieved 19 November 2021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Eschmeyer, W.N. and R. Fricke, eds. lymma, Raja Archived 2012-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. Catalog of Fishes electronic version (January 15, 2010). Retrieved on February 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Van der Elst, R. (1993). A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa (third ed.). Struik. p. 52. ISBN 978-1-86825-394-4.

- ^ Eschmeyer, W.N. and R. Fricke, eds. Taeniura Archived 2012-02-21 at the Wayback Machine. Catalog of Fishes electronic version (January 15, 2010). Retrieved on February 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2009). "Taeniura lymma " in FishBase. November 2009 version.

- ^ Lovejoy, N.R. (1996). "Systematics of myliobatoid elasmobranchs: with emphasis on the phylogeny and historical biogeography of neotropical freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygonidae: Rajiformes)" (PDF). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 117 (3): 207–257. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.1996.tb02189.x. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-08. Retrieved 2010-02-21 .

- ^ a b Randall, J.E. & J.P. Hoover (1995). Coastal Fishes of Oman. University of Hawaii Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-0-8248-1808-1.

- ^ a b c d Ferrari, A. & A. Ferrari (2002). Sharks . Firefly Books. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-1-55209-629-1.

- ^ a b c d Last, P.R. & L.J.V. Compagno (1999). "Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae". In Carpenter, K.E. & V.H. Niem (eds.). The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific. Vol. 3. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. pp. 1479–1505. ISBN 978-92-5-104302-8.

- ^ a b Heemstra, P. & E. Heemstra (2004). Coastal Fishes of Southern Africa . NISC and SAIAB. p. 84. ISBN 978-1-920033-01-9.

- ^ Van Der Elst R.; D. King (2006). A Photographic Guide to Sea Fishes of Southern Africa . Struik. p. 17. ISBN 978-1-77007-345-6.

- ^ a b c d e Michael, S.W. (1993). Reef Sharks and Rays of the World – A Guide To Their Identification, Behavior and Ecology. Sea Challengers. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-930118-18-1.

- ^ a b c d Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Bluespotted Ribbontail Ray Archived 2016-01-04 at the Wayback Machine. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on November 13, 2009.

- ^ a b Miller, J. (2002). Taeniura lymma (On-line). Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved on November 13, 2009.

- ^ a b c Last, P.R. & J.D. Stevens (2009). Sharks and Rays of Australia (second ed.). Harvard University Press. pp. 459–460. ISBN 978-0-674-03411-2.

- ^ Mann, J. & B. Sargeant (2003). "Like mother, like calf: the ontogeny of foraging traditions in wild Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.)". In Fragaszy, D.M. & S. Perry (eds.). The Biology of Traditions: Models and Evidence. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-81597-0.

- ^ Jensen, K. (June 2006). "A new species of Aberrapex Jensen, 2001 (Cestoda: Lecanicephalidea) from Taeniura lymma (Forsskal) (Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae) from off Sabah, Malaysia". Systematic Parasitology. 64 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1007/s11230-005-9026-2. PMID 16612652.

- ^ Saoud, M.F.A. (1963). "On a new cestode, Anthobothrium taeniuri n. sp. (Tetraphyllidea) from the Red Sea Sting Ray and the relationship between Anthobothrium van Beneden, 1850, Rhodobothrium Linton, 1889 and Inermiphyllidium Riser, 1955". Journal of Helminthology. 37 (1–2): 135–144. doi:10.1017/S0022149X00019696. PMID 13976441.

- ^ Ramadan, M.M. (1986). "Cestodes of the genus Cephalobothrium Shipley and Hornel, 1906 (Lecanicephaliidae), with description of C. ghardagense n. sp. and C. taeniurai n. sp. from the Red Sea fishes". Japanese Journal of Parasitology. 35 (1): 11–15.

- ^ Tyler, G.A. (II) (2006). "Tapeworms of elasmobranchs (part II) a monograph on the Diphyllidea (Platyhelminthes, Cestoda)". Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum. 20: i–viii, 1–142.

- ^ Saoud, M.F.A.; M.M. Ramadan & S.I. Hassan (1982). "On Echinobothrium helmymohamedi n. sp. (Cestoda: Diphyllidea): a parasite of the sting ray Taeniura lymma from the Red Sea". Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology. 12 (1): 199–207. PMID 7086222.

- ^ Palm, H.W. & I. Beveridge (May 2002). "Tentaculariid cestodes of the order Trypanorhyncha (Platyhelminthes) from the Australian region". Records of the South Australian Museum. 35 (1): 49–78.

- ^ Hassan, S.H. (December 1982). "Polypocephalus saoudi n. sp. Lecanicephalidean cestode from Taeniura lymma in the Red Sea". Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology. 12 (2): 395–401. PMID 7153551.

- ^ Ramadan, M.M. (1984). "A review of the cestode genus Rhinebothrium Linton, 1889 (Tetraphyllidae), with a description of two new species of the sting ray Taeniura lymma from the Red Sea". Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology. 14 (1): 85–94. PMID 6736718.

- ^ Cribb, B.W.; Whittington, Ian D. (2004). "Anterior adhesive areas and adjacent secretions in the parasitic flatworms Decacotyle lymmae and D. tetrakordyle (Monogenea: Monocotylidae) from the gills of stingrays". Invertebrate Biology. 123 (1): 68–77. doi:10.1111/j.1744-7410.2004.tb00142.x.

- ^ Chisholm, L.A. & I.D. Whittington (1999). "Empruthotrema quindecima sp. n. (Monogenea: Monocotylidae) from the nasal fossae of Taeniura lymma (Dasyatididae) from Heron Island and Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef, Queensland, Australia". Folia Parasitologica. 46 (4): 274–278.

- ^ Whittington, I.D. & B.W. Cribb (April 1998). "Glands associated with the anterior adhesive areas of the monogeneans, Entobdella sp. and Entobdella australis (Capsalidae) from the skin of Himantura fai and Taeniura lymma (Dasyatididae)". International Journal for Parasitology. 28 (4): 653–665. doi:10.1016/S0020-7519(98)00016-2. PMID 9602390.

- ^ Agrawal, N.; L.A. Chisholm & I.D. Whittington (February 1996). "Pseudohexabothrium taeniurae n. sp. (Monogenea: Hexabothriidae) from the gills of Taeniura lymma (Dasyatididae) from the Great Barrier Reef, Australia". The Journal of Parasitology. 82 (1): 131–136. doi:10.2307/3284128. JSTOR 3284128. PMID 8627482.

- ^ Saoud, M.F.A. & M.M. Ramadan (1984). "Two trematodes of genus Pedunculacetabulum Yamaguti, 1934 from Red Sea fishes". Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology. 14 (2): 321–328. PMID 6512282.

- ^ Razarihelisoa, M. (1959). "Sur quelques trematodes digenes de poissons de Nossibe (Madagascar)". Bulletin de la Société Zoologique de France. 84: 421–434.

- ^ Sprent, J.F.A. (1990). "Some ascaridoid nematodes of fishes: Paranisakis and Mawsonascaris n. g". Systematic Parasitology. 15 (1): 41–63. doi:10.1007/bf00009917.

- ^ Kornicker, L.S. (1986). "Redescription of Sheina orri Harding, 1966, a myodocopid ostracode collected on fishes off Queensland, Australia". Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington. 99 (4): 639–646.

- ^ Burreson, E.M. (1989). "Haematozoa of fishes from Heron I., Australia, with the description of two new species of Trypanosoma". Australian Journal of Zoology. 37 (1): 15–23. doi:10.1071/ZO9890015.

- ^ Burgess, W.E.; H.R. Axelrod & R.E. Hunziker (2000). Dr. Burgess's Atlas of Marine Aquarium Fishes (third ed.). T.F.H. Publications. p. 676. ISBN 978-0-7938-0575-4.

- ^ Ferreira, A.S. (2013), Breeding and juvenile growth of the ribbontail stingray Taeniura lymma at Oceanário de Lisboa (PDF), University of Lisbon

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Bluespotted ribbontail ray: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia EN

The bluespotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma) is a species of stingray in the family Dasyatidae. Found from the intertidal zone to a depth of 30 m (100 ft), this species is common throughout the tropical Indian and western Pacific Oceans in nearshore, coral reef-associated habitats. It is a fairly small ray, not exceeding 35 cm (14 in) in width, with a mostly smooth, oval pectoral fin disc, large protruding eyes, and a relatively short and thick tail with a deep fin fold underneath. It can be easily identified by its striking color pattern of many electric blue spots on a yellowish background, with a pair of blue stripes on the tail.

At night, small groups of bluespotted ribbontail rays follow the rising tide onto sandy flats to root for small benthic invertebrates and bony fishes in the sediment. When the tide recedes, the rays separate and withdraw to shelters on the reef. Reproduction is aplacental viviparous, with females giving birth to litters of up to seven young. This ray is capable of injuring humans with its venomous tail spines, though it prefers to flee if threatened. Because of its beauty and size, the bluespotted ribbontail ray is popular with private aquarists despite being poorly suited to captivity.

- license

- cc-by-sa-3.0

- copyright

- Wikipedia authors and editors

Raie pastenague à taches bleues

provided by wikipedia FR

Taeniura lymma

La raie pastenague à taches bleues ou pastenague queue à ruban ( Taeniura lymma ) est une espèce de poissons cartilagineux de la famille des Dasyatidae. Cette raie est présente de la zone intertidale jusqu'à une profondeur de 30 m. Elle est fréquente dans les habitats côtiers ou à proximité de récifs coralliens des océans Indien et Pacifique occidental. Cette raie assez petite ne mesure pas plus de 35 cm de largeur : le disque pectoral est ovale et largement régulier, les grands yeux sont protubérants, la queue courte et épaisse surmonte un repli encaissé dans la nageoire. Le poisson est facilement reconnaissable à son éclatant jeu de couleurs qui consiste en de nombreux points bleus électriques sur un fond jaunâtre avec une queue striée de deux bandes bleues.

La nuit tombée, la raie pastenague à taches bleues rejoint des congénères et forme un petit groupe pour chasser sur des plaines sablonneuses en se laissant porter par la marée montante ; elle se nourrit d'invertébrés benthiques ainsi que de poissons osseux. Quand la marée est descendante, la raie se sépare de son groupe et se retire à l'abri sur un récif. La reproduction est ovovivipare : la femelle peut mettre au monde jusqu'à sept petits. Cette raie est en mesure d'infliger à l'homme une piqûre douloureuse grâce aux épines venimeuses situées sur sa queue ; la fuite est cependant préférée en cas de menace. Malgré ses inaptitudes à la vie en captivité, la beauté et la taille du poisson sont des attraits pour les aquariophiles. En raison de la détérioration généralisée de son habitat (récifs coralliens) et de la menace que représente la pêche intensive, l'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN) range la raie pastenague à taches bleues parmi les espèces « Quasi menacées » [2] .

Sommaire

- 1 Description

- 2 Répartition géographique et habitat

- 3 Taxinomie et phylogénie

- 4 Biologie et écologie

- 5 Relations avec l'homme

- 6 Annexes

- 6.1 Références taxinomiques

- 7 Notes et références

Description

La coloration de la raie pastenague à taches bleues est facilement reconnaissable.

La raie pastenague à taches bleues atteint 80 cm de long, 35 cm de large et pèse jusqu'à 5 kg [3] , [4] .

Le disque formé par la nageoire pectorale adopte une forme ovale, il est environ un cinquième plus long que large.

Le museau est arrondi ou légèrement anguleux. Les stigmates sont situés immédiatement derrière les grands yeux protubérants. Un étroit rabat de peau chevauchant la gueule fait la jonction entre les narines : la bordure postérieure de ce rabat de peau est ourlée. La mâchoire inférieure se creuse au milieu et est cernée de larges sillons situés de chaque côté de la gueule. Chacune des mâchoires compte entre 15 et 24 rangées de dents agencées à la façon d'un pavement ; deux grandes papilles sont disposées sur le plancher de la gueule [5] , [6] .

Les nageoires pelviennes sont étroites et anguleuses. La queue épaisse et pendante est environ une fois et demie plus longue que le disque : elle supporte deux (plus rarement une seule) épines crénelées loin derrière la base de la queue. Un profond repli de nageoire est visible sur la surface ventrale, il se prolonge jusqu'au bout de la queue ; une crête peu marquée se dessine sur la surface supérieure [7] , [6] .

Raie pastenague à taches bleues (île de Ko Tao, Thaïlande)

À l'exception de quelques petites épines au milieu de la surface dorsale, la peau est lisse [6] . La coloration dorsale est éclatante : elle consiste en de nombreuses taches circulaires bleu électrique sur un fond ocre ou verdâtre. Les taches sont de tailles différentes mais elles se rétrécissent aux bordures du disque.

La queue présente deux bandes du même bleu qui s'élancent de chaque côté de l'organe jusqu'aux épines. Il arrive que des spécimens rencontrés au large de l'Afrique australe ne disposent pas de ces deux bandes [8] .

Les yeux sont d'un jaune brillant, la surface ventrale est blanche [5] , [9] .

Répartition géographique et habitat

Raie pastenague à taches bleues (Sabah, Malaisie)

La raie pastenague à taches bleues vit dans les eaux côtières de la zone tropicale du bassin Indo-Pacifique. Dans l'océan Indien, sa présence est établie depuis l'Afrique du Sud jusqu'à la Péninsule Arabique et l'Asie du Sud-Est : cela comprend Madagascar, Maurice, Zanzibar, les Seychelles, le Sri Lanka ainsi que les Maldives. Il est rare de rencontrer ce poisson dans le golfe Persique et dans le golfe d'Oman [1] , [7] . Dans l'océan Pacifique, l'espèce est présente des Philippines jusqu'aux côtes septentrionales de l'Australie ; elle est également aperçue autour de nombreuses îles de Mélanésie et de Polynésie, l'extrémité orientale de la répartition étant les îles Salomon [1] . La raie pastenague à taches bleues se rencontre rarement au-delà de 30 m de profondeur : ce poisson démersal apprécie en effet les récifs coralliens et les plaines sablonneuses qui les bordent, ainsi que les herbiers marins [1] . Il est souvent aperçu dans la zone intertidale et dans des mares résiduelles [9] . Tous les étés, un nombre considérable de raies pastenagues à taches bleues se rend près des côtes sud-africaines [5] .

Taxinomie et phylogénie

La raie pastenague à taches bleues est originellement décrite par le naturaliste suédois Pehr Forsskål sous le nom Raja lymma dans son ouvrage Descriptiones Animalium quae in itinere ad maris australis terras per annos 1772, 1773, et 1774 suscepto collegit, observavit, et delineavit Joannes Reinlioldus Forster, etc., curante Henrico Lichtenstein publié en 1775. L'épithète spécifique lymma signifie « boue » [5] . Forsskål ne désigne pas de spécimen type. En 1837, les biologistes allemands Johannes Peter Müller et Friedrich Gustav Jakob Henle créent le genre Taeniura qui doit accueillir l'espèce Trygon ornatus ; cette dernière est maintenant reconnue comme un synonyme plus récent [3] .

Un autre nom vulgaire utilisé en français pour désigner cette espèce est pastenague queue à ruban ; celui-ci se rencontre plus rarement [3] , [10] . Une étude morphologique publiée en 1996 suggère que la raie pastenague à taches bleues est plus proche des raies du genre Himantura vivant près des côtes américaines ainsi que des raies d'eau douce de la famille Potamotrygonidae, plutôt que de la raie à taches noires (T. meyeni) avec qui elle partage son genre. Celle-ci serait en effet affiliée au genre Dasyatis et aux raies du genre Himantura vivant dans le bassin Indo-Pacifique [11] .

Biologie et écologie

La pastenague à taches bleues se cache parmi les coraux durant la journée.

La raie pastenague à taches bleues est habituellement solitaire durant la journée qu'elle passe cachée à l'intérieur de cavernes, à l'abri sous un récif corallien ou sous des débris divers (notamment des épaves) ; bien souvent, seule sa queue est visible [9] , [6] , [12] . Contrairement à beaucoup d'espèces proches, il est rare que ce poisson s'enfonce dans le sable [13] . La nuit, de petits groupes se forment et, suivant la marée montante, se dirigent vers des plaines sablonneuses peu profondes où se nourrir. La raie creuse les fonds sablonneux à la recherche de mollusques, de polychètes, de crevettes, de crabes et de petits poissons osseux benthiques ; quand une proie est découverte, elle est piégée sous le corps de la raie est dirigée vers sa gueule à l'aide du disque. Certains poissons, comme ceux issus de la famille Mullidae, suivent le groupe lors de sa chasse et se nourrissent des proies restantes [8] , [14] .

La période de reproduction de l'espèce s'étend de la fin du printemps jusqu'en été : le mâle suit la femelle et s'y accroche en mordant son disque, il se maintient sur elle afin de procéder à la copulation [14] . Il existe un exemple documenté d'un mâle se tenant sur le disque d'un autre mâle de plus petite taille de l'espèce Neotrygon kuhlii (pastenague à points bleus), il pourrait s'agir d'une identification erronée. Des rassemblements de mâles adultes ont été observés en eaux peu profondes, cela pourrait être lié à la reproduction [12] . Comme les autres poissons apparentés, cette espèce est ovovivipare : lors du développement intra-utérin, les embryons se nourrissent de vitellus puis d'un liquide histotrophe contenant du mucus, de la graisse ainsi que des protéines, il s'agit d'une sorte de « lait utérin » sécrété par la mère. La durée de la gestation n'est pas connue avec précision, on pense cependant qu'elle est comprise entre quatre et douze mois. La femelle met au monde de trois à sept petits [15] qui mesurent environ 13 ou 14 cm de large : le petit est un portrait réduit du poisson à la taille adulte [13] , [16] . Le mâle arrive à maturité sexuelle quand la largeur du disque atteint 20 ou 21 cm ; la donnée similaire pour la femelle est inconnue [3] , [16] .

La liste des prédateurs connus de la raie pastenague à tache bleues comprend les requins-marteaux et les dauphins du genre Tursiops ; il est possible que l'espèce soit la proie d'autres grands poissons et mammifères marins [13] , [17] . Quand elle est menacée, cette raie a tendance à fuir en zigzag afin de semer ses poursuivants [9] . De nombreux parasites de l'espèce ont été identifiés : les cestodes Aberrapex manjajiae [18] , Anthobothrium taeniuri [19] , Cephalobothrium taeniurai [20] , Echinobothrium elegans et E. helmymohamedi [21] , [22] , Kotorelliella jonesi [23] , Polypocephalus saoudi [24] , Rhinebothrium ghardaguensis et R. taeniuri [25] , les monogènes Decacotyle lymmae [26] , Empruthotrema quindecima [27] , Entobdella australis [28] , et Pseudohexabothrium taeniurae [29] , les vers plats Pedunculacetabulum ghardaguensis et Anaporrhutum albidum [30] , [31] , le nématode Mawsonascaris australis [32] , le copépode Sheina orri [33] , et le protozoaire Trypanosoma taeniurae [34] . Cette raie a été observée profitant des « services » du labre nettoyeur commun : elle indique son accord en soulevant les rebords du disque et les nageoires pelviennes [12] .

Relations avec l'homme

La raie pastenague à taches bleues est généralement d'un tempérament craintif et s'éloigne des plongeurs qu'elle aperçoit ; en revanche, si elle se sent menacée, elle est capable d'infliger une blessure très douloureuse à l'homme à l'aide des épines venimeuses qu'elle porte sur sa queue [13] . En raison de son apparence attrayante ainsi que de sa taille relativement modeste, ce poisson est celui de l'ordre des Myliobatiformes que l'on retrouve le plus fréquemment chez les aquariophiles [35] . Cependant, il est rare que la raie s'adapte à ce nouveau milieu et très peu d'aquariophiles parviennent à maintenir un spécimen en vie bien longtemps [12] . Il est courant que la raie pastenague à taches bleues refuse de se nourrir dans l'aquarium ; fréquemment, des spécimens apparemment en bonne santé arrêtent de se nourrir ou meurent de façon inexplicable [12] .

La chair du poisson est consommée en Afrique de l'Est, en Asie du Sud-Est et en Australie. Cette prise est soit celle recherchée, soit une prise accessoire ; la raie est capturée à l'aide d'un filet maillant, d'une palangre, d'une pointe ou d'une nasse [1] , [16] .

L'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN) donne à la raie pastenague à taches bleues le statut d'espèce « Quasi menacée ». Même si elle se rencontre fréquemment et qu'elle occupe une vaste répartition, cette espèce souffre de la dégradation persistante de son habitat partout dans sa zone de distribution : les récifs coralliens à proximité desquels elle vit sont mis en danger par des pratiques halieutiques destructrices recourant au cyanure et à la dynamite. Enfin, la pêche locale destinée à l'aquariophilie, ainsi que la pêche sous une forme commerciale ou artisanale sont des menaces importantes [1] .

Annexes

Références taxinomiques

- (fr+en) Référence FishBase :

- (fr+en) Référence ITIS : Taeniura lymma (Forsskål, 1775)

- (en) Référence Animal Diversity Web : Taeniura lymma

- (en) Référence NCBI : Taeniura lymma (taxons inclus)

- (en) Référence UICN : espèce Taeniura lymma (Forsskål, 1775) (consulté le 31 mai 2015)

- (en) Référence Catalogue of Life : Taeniura lymma (Forsskål, 1775) (consulté le 16 décembre 2020)

- (en) Référence Fonds documentaire ARKive : Taeniura lymma

Notes et références

- (en) Cet article est partiellement ou en totalité issu de l'article de Wikipédia en anglais intitulé .

- ↑ a b c d e et f (en) Compagno, L.J.V., « Taeniura lymma », sur iucnredlist.org, 2005 (consulté en février 2015)

- ↑ Muséum Aquarium de Nancy, « Pastenague à points bleus », sur especeaquatique.museumaquariumdenancy.eu (consulté le 25 décembre 2020)

- ↑ a b c et d (en) Froese, R. et D. Pauly, « Taeniura lymma (Forsskål, 1775) Ribbontail stingray », sur FishBase.org, 2014 (consulté en février 2015)

- ↑ (en) Van Der Elst, R. and D. King, A Photographic Guide to Sea Fishes of Southern Africa, Struik, 2006 (ISBN 1-77007-345-0), p. 17

- ↑ a b c et d (en) Van der Elst, R., A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa, Struik, 1993 (ISBN 1-86825-394-5), p. 52

- ↑ a b c et d (en) Last, P.R. and L.J.V. Compagno, The Living Marine Resources of the Western Central Pacific (Volume 3), Rome, Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations, 1999, 1479–1505 p. (ISBN 92-5-104302-7) , « Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae »

- ↑ a et b (en) Randall, J.E. and J.P. Hoover, Coastal Fishes of Oman, University of Hawaii Press, 1995 (ISBN 0-8248-1808-3), p. 47

- ↑ a et b (en) Heemstra, P. and E. Heemstra, Coastal Fishes of Southern Africa, NISC and SAIAB, 2004 (ISBN 1-920033-01-7), p. 84

- ↑ a b c et d (en) Ferrari, A. and A. Ferrari, Sharks, Firefly Books, 2002, 214–215 p. (ISBN 1-55209-629-7)

- ↑ (en) Sommer, C., Schneider W. et Poutiers J.-M., The Living Marine Resources of Somalia, Rome, FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS, 1996 (ISBN 92-5-103742-6, lire en ligne) .

- ↑ (en) Lovejoy, N.R., « Systematics of myliobatoid elasmobranchs: with emphasis on the phylogeny and historical biogeography of neotropical freshwater stingrays (Potamotrygonidae: Rajiformes) », Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society , vol. 117, no 3, 1996, p. 207–257 (DOI , lire en ligne)

- ↑ a b c d et e (en) Michael, S.W., Reef Sharks and Rays of the World – A Guide To Their Identification, Behavior and Ecology, Sea Challengers, 1993 (ISBN 0-930118-18-9), p. 107

- ↑ a b c et d (en) Bester, C., « Bluespotted ribbontail ray », sur Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department (consulté en février 2015)

- ↑ a et b (en) Miller, J., « Taeniura lymma (On-line) », sur animaldiversityweb.com, 2002 (consulté en février 2015)

- ↑ Collectif (trad. Josette Gontier), Le règne animal, Gallimard Jeunesse, octobre 2002, 624 p. (ISBN 2-07-055151-2), Pastenague mouchetée page 477

- ↑ a b et c (en) Last, P.R. and J.D. Stevens, Sharks and Rays of Australia, Cambridge (Mass.), Harvard University Press, 2009, 459–460 p. (ISBN 978-0-674-03411-2 et 0-674-03411-2)

- ↑ (en) Mann, J. and B. Sargeant, The Biology of Traditions : Models and Evidence, Cambridge University Press, 2003 (ISBN 0-521-81597-5) , « Like mother, like calf: the ontogeny of foraging traditions in wild Indian Ocean bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops sp.) »

- ↑ (en) Jensen, K., « A new species of Aberrapex Jensen, 2001 (Cestoda: Lecanicephalidea) from Taeniura lymma (Forsskal) (Myliobatiformes: Dasyatidae) from off Sabah, Malaysia », Systematic Parasitology , vol. 64, no 2, juin 2006, p. 117–123 (DOI , lire en ligne)

- ↑ (en) Saoud, M.F.A., « On a new cestode, Anthobothrium taeniuri n. sp. (Tetraphyllidea) from the Red Sea Sting Ray and the relationship between Anthobothrium van Beneden, 1850, Rhodobothrium Linton, 1889 and Inermiphyllidium Riser, 1955 », Journal of Helminthology , vol. 37, 1963, p. 135–144 (DOI )

- ↑ (en) Ramadan, M.M., « Cestodes of the genus Cephalobothrium Shipley and Hornel, 1906 (Lecanicephaliidae), with description of C. ghardagense n. sp. and C. taeniurai n. sp. from the Red Sea fishes », Japanese Journal of Parasitology , vol. 35, no 1, 1986, p. 11–15

- ↑ (en) Tyler, G.A. (II), « Tapeworms of elasmobranchs (part II) a monograph on the Diphyllidea (Platyhelminthes, Cestoda) », Bulletin of the University of Nebraska State Museum , vol. 20, 2006, i–viii, 1–142

- ↑ (en) Saoud, M.F.A., M.M. Ramadan and S.I. Hassan, « On Echinobothrium helmymohamedi n. sp. (Cestoda: Diphyllidea): a parasite of the sting ray Taeniura lymma from the Red Sea », Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology , vol. 12, no 1, 1982, p. 199–207

- ↑ (en) Palm, H.W. and I. Beveridge, « Tentaculariid cestodes of the order Trypanorhyncha (Platyhelminthes) from the Australian region », Records of the South Australian Museum , vol. 35, no 1, mai 2002, p. 49–78

- ↑ (en) Hassan, S.H., « Polypocephalus saoudi n. sp. Lecanicephalidean cestode from Taeniura lymma in the Red Sea », Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology , vol. 12, no 2, décembre 1982, p. 395–401

- ↑ (en) Ramadan, M.M., « A review of the cestode genus Rhinebothrium Linton, 1889 (Tetraphyllidae), with a description of two new species of the sting ray Taeniura lymma from the Red Sea », Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology , vol. 14, no 1, 1984, p. 85–94

- ↑ (en) Cribb, B.W. et Ian D. Whittington, « Anterior adhesive areas and adjacent secretions in the parasitic flatworms Decacotyle lymmae and D. tetrakordyle (Monogenea: Monocotylidae) from the gills of stingrays », Invertebrate Biology , vol. 123, no 1, 2004, p. 68–77 (DOI , lire en ligne)

- ↑ (en) Chisholm, L.A. and I.D. Whittington, « Empruthotrema quindecima sp. n. (Monogenea: Monocotylidae) from the nasal fossae of Taeniura lymma (Dasyatididae) from Heron Island and Lizard Island, Great Barrier Reef, Queensland, Australia », Folia Parasitologica , vol. 46, no 4, 1999, p. 274–278 (lire en ligne)

- ↑ (en) Whittington, I.D. and B.W. Cribb, « Glands associated with the anterior adhesive areas of the monogeneans, Entobdella sp. and Entobdella australis (Capsalidae) from the skin of Himantura fai and Taeniura lymma (Dasyatididae) », International Journal for Parasitology , vol. 28, no 4, avril 1998, p. 653–665 (DOI , lire en ligne)

- ↑ (en) Agrawal, N., L.A. Chisholm and I.D. Whittington, « Pseudohexabothrium taeniurae n. sp. (Monogenea: Hexabothriidae) from the gills of Taeniura lymma (Dasyatididae) from the Great Barrier Reef, Australia », The Journal of Parasitology , vol. 82, no 1, février 1996, p. 131–136 (DOI )

- ↑ (en) Saoud, M.F.A. and M.M. Ramadan, « Two trematodes of genus Pedunculacetabulum Yamaguti, 1934 from Red Sea fishes », Journal of the Egyptian Society of Parasitology , vol. 14, no 2, 1984, p. 321–328

- ↑ Razarihelisoa, M., « Sur quelques trematodes digenes de poissons de Nossibe (Madagascar) », Bulletin de la Société Zoologique de France, vol. 84, 1959, p. 421–434

- ↑ (en) Sprent, J.F.A., « Some ascaridoid nematodes of fishes: Paranisakis and Mawsonascaris n. g », Systematic Parasitology , vol. 15, no 1, 1990, p. 41–63 (DOI , lire en ligne)

- ↑ (en) Kornicker, L.S., « Redescription of Sheina orri Harding, 1966, a myodocopid ostracode collected on fishes off Queensland, Australia », Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington , vol. 99, no 4, 1986, p. 639–646

- ↑ (en) Burreson, E.M., « Haematozoa of fishes from Heron I., Australia, with the description of two new species of Trypanosoma », Australian Journal of Zoology , vol. 37, no 1, 1989, p. 15–23 (DOI )

- ↑ (en) Burgess, W.E., H.R. Axelrod and R.E. Hunziker, Dr. Burgess's Atlas of Marine Aquarium Fishes, T.F.H. Publications, 2000 (ISBN 0-7938-0575-9), p. 676

- license

- fr

- copyright

- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Raie pastenague à taches bleues: Brief Summary

provided by wikipedia FR

Taeniura lymma

La raie pastenague à taches bleues ou pastenague queue à ruban (Taeniura lymma) est une espèce de poissons cartilagineux de la famille des Dasyatidae. Cette raie est présente de la zone intertidale jusqu'à une profondeur de 30 m. Elle est fréquente dans les habitats côtiers ou à proximité de récifs coralliens des océans Indien et Pacifique occidental. Cette raie assez petite ne mesure pas plus de 35 cm de largeur : le disque pectoral est ovale et largement régulier, les grands yeux sont protubérants, la queue courte et épaisse surmonte un repli encaissé dans la nageoire. Le poisson est facilement reconnaissable à son éclatant jeu de couleurs qui consiste en de nombreux points bleus électriques sur un fond jaunâtre avec une queue striée de deux bandes bleues.

La nuit tombée, la raie pastenague à taches bleues rejoint des congénères et forme un petit groupe pour chasser sur des plaines sablonneuses en se laissant porter par la marée montante ; elle se nourrit d'invertébrés benthiques ainsi que de poissons osseux. Quand la marée est descendante, la raie se sépare de son groupe et se retire à l'abri sur un récif. La reproduction est ovovivipare : la femelle peut mettre au monde jusqu'à sept petits. Cette raie est en mesure d'infliger à l'homme une piqûre douloureuse grâce aux épines venimeuses situées sur sa queue ; la fuite est cependant préférée en cas de menace. Malgré ses inaptitudes à la vie en captivité, la beauté et la taille du poisson sont des attraits pour les aquariophiles. En raison de la détérioration généralisée de son habitat (récifs coralliens) et de la menace que représente la pêche intensive, l'Union internationale pour la conservation de la nature (UICN) range la raie pastenague à taches bleues parmi les espèces « Quasi menacées ».

- license

- fr

- copyright

- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

꽁지가오리

provided by wikipedia 한국어 위키백과

꽁지가오리(Bluespotted ribbontail ray)는 색가오리과의 한 종이다. 조간대에서 깊이 30m까지에서 발견되고, 열대 인도양 지방, 서태평양 지방의 산호초 지역에 분포한다. 35cm의 길이를 넘지 않은 작은 체구를 가지고 있고, 매끄러운 타원형의 가슴지느러미, 큰 퉁방울눈, 상대적으로 짧고 굵은 꼬리를 가지고 있다. 몸은 노란색 바탕에 파란 색 무늬이고, 꼬리는 파란색 줄무늬로 되어 있어서, 다른 가오리와 쉽게 구별할 수 있다.

- license

- ko

- copyright

- http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/

Description

provided by World Register of Marine Species

Found inshore, at depths less than 20 m (Ref. 9840). Migrates in groups into shallow sandy areas during the rising tide to feed on molluscs, worms, shrimps, and crabs; disperses on falling tide to seek shelter in caves and under ledges (Ref. 6871). Disk width about 95 cm. Reports of specimens reaching 240 cm TL are probably inaccurate (Ref. 6871). Taken mainly by traditional fishermen (Ref. 9840).

- license

- cc-by-4.0

- copyright

- WoRMS Editorial Board

Source: https://eol.org/pages/46560945/articles

0 Response to "What Is a Special Thing the Blue Spotted Sting Ray Can Do"

Post a Comment